Didi: A Great Business That Still Leaves Me Uneasy

Strong fundamentals, lingering doubts.

My Recent Meeting With Didi Left Me Uneasy

Let’s start with a confession: I can’t imagine my life without DiDi. I love their service. They’re the very reason I sold my car, and I’m not thinking for a minute about buying another one. I like the business too, I like the whole setup with trading over the counter and having the option of being relisted in Hong Kong. I’m the second-highest tier user, and everyone on my company’s staff uses their service.

I’m giving you this background so you understand that what follows comes from a place of affection, not animosity.

But a couple of weeks ago, I had a conversation with DiDi’s investor relations team that left me feeling... let’s say uneasy. The kind of uneasy you get when someone you trust tells you not to worry about something that absolutely deserves worrying about.

To be clear, Didi’s investor relations team was fully professional and genuinely helpful — which, in fairness, isn’t something one can take for granted when dealing with Chinese companies. My concern isn’t with the IR team itself, but with what was actually said.

I’ve been mulling this over ever since, but because DiDi updates are among the most requested from readers, and because some news I read a few days ago finally convinced me to put this in writing, here we are.

China business: Going Strong

Didi’s core business the China business looks good. I have written about it before. Take rates are improving. EBITDA margins are heading in the right direction. User stickiness remains strong. Market share is defensible. Competitors like Caocao (the number two player 5.4% market share) have done precisely nothing of consequence. In fact, according to Caocao’s (HK:2643) own IPO prospectus, DiDi commands roughly 70% market share. That’s the kind of dominance that comes with serious scale advantages and network effects. Even the aggregators like Gaude (Alibaba’s Map service), while theoretically a threat, seem more like background noise than an existential crisis at the moment.

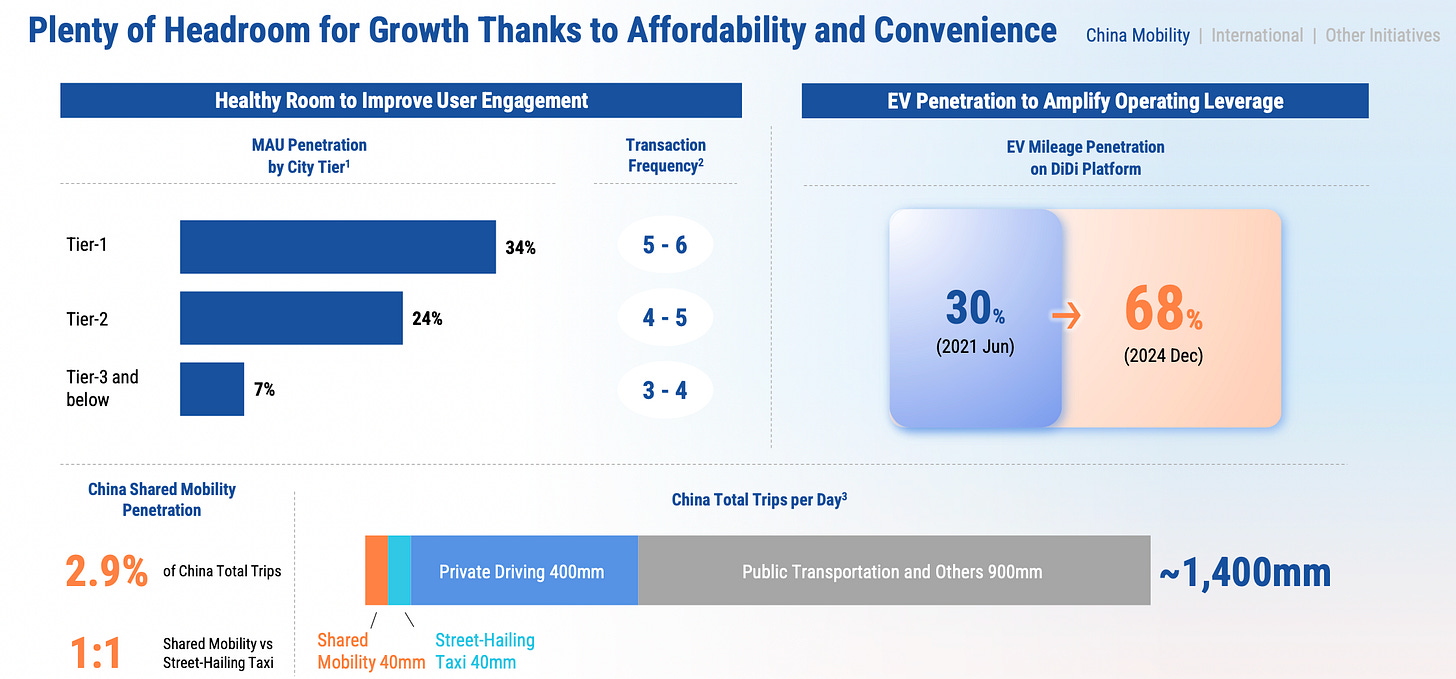

There’s still significant room for growth in lower-tier cities. IR told me that even in mature markets such as Beijing and Shanghai, they’re still seeing 6–7% year-over-year growth in trip volume, while second-tier cities are growing around 10%, and lower-tier cities even faster, as they continue to gain market share from traditional taxis. Compared with international peers like Uber and Lyft, DiDi’s share of total trips remains much smaller, leaving ample space for expansion.

From what I’ve observed firsthand in recent years—speaking with people across different demographics—the social status once associated with owning a large car has declined sharply. As a result, more users are likely to shift to DiDi, since on a pure cost basis, using DiDi is far cheaper than owning a car once you factor in parking fees, maintenance, repairs, and the many hidden costs of ownership. IR told me that in major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, they estimate that using Didi costs about 30–40% of what it would cost to own a car — a figure I find entirely believable.

Didi is not only cheaper than owning a car, but also far more convenient — you don’t have to drive through traffic yourself or waste time finding parking; the driver simply picks you up wherever you are and drops you off right at your destination.

As of now, I’m fairly optimistic about the China business. Management expects around 10% volume growth next year, along with slightly better margins, which seems reasonable to me. If nothing major changes, I’m confident DiDi will maintain stable growth—perhaps not at the high rates of the past—but continue to dominate the field while steadily improving its margins.

The Ride-Hailing War Is Over (Probably)

It appears the great ride-hailing war in China has reached an end. The battlefield has been surveyed, the casualties counted, and everyone seems content to hold their territory. So the market leader should now enjoy its scale advantage.

Except… I’ve thought this before.

I thought the same thing about Meituan’s food delivery dominance. Then JD and Alibaba decided to throw logic out the window and burn billions of dollars to gain market share. I genuinely did not expect rational economic actors to behave that irrationally. But it’s China—and they did. And they might again.

The saving grace for Didi is that ride-hailing doesn’t seem to be the strategic focus of any of the big boys. Food delivery? Sure, that’s core if you’re already in retail. It’s adjacent, it’s logical, it’s maybe worth a subsidy war. But ride-hailing sits in a different category altogether. Even Meituan, which once tried to challenge DiDi, has pulled back.

Still, this remains a very China-specific risk—one that DiDi’s management simply can’t prepare for if another player decides to throw rationality out the window. I mention this because it’s something one must always keep in mind and watch closely in China. For now, though, there’s no sign of irrational competition.

That said, I’m confident in the China business. It appears stable—for now. Which, in Chinese tech terms, means “probably fine until it very suddenly isn’t.”

I’ve covered the bright side. What follows is the part that makes me nervous.