Take that efficient-market hypothesis!

A beautiful theory slain by ugly Chinese stocks

Measuring Perceptions: Evaluating Chinese Economic Sentiment Against Global Views

I often get asked about how people in China view their economy right now. Of course, I could share some personal anecdotes and things I've picked up from talking to people or business owners. It's a tricky question, but I've found a more objective and direct way to approach this: by comparing the share prices of large Chinese companies that are well-covered by analysts and listed in both Hong Kong and mainland China, and are included in the Stock Connect.

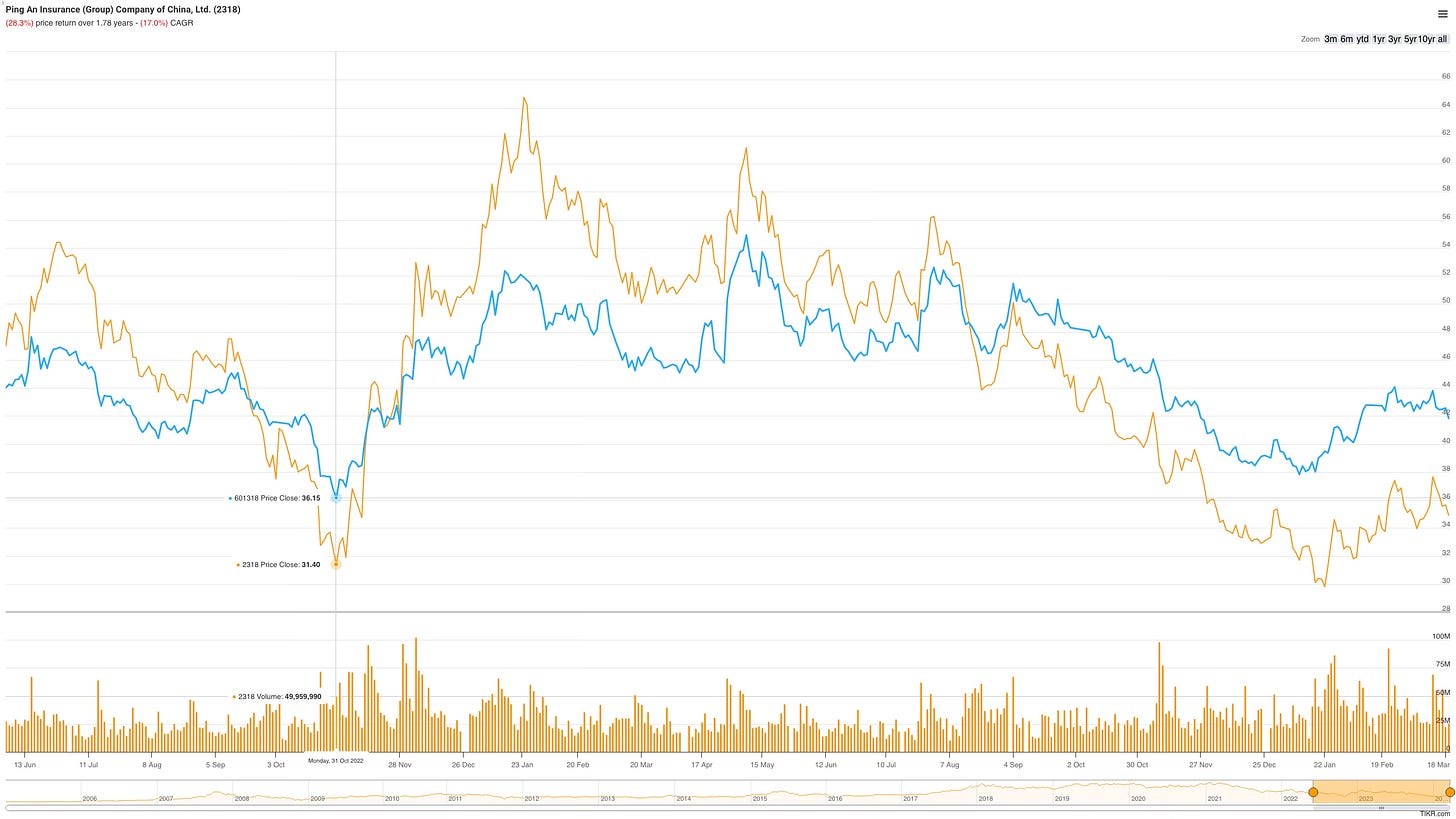

Ideally, shares of the same company should trade at similar prices across these exchanges, once you account for differences such as taxes on dividends. Typically, the prices of H-shares and A-shares move together with minor discrepancies. However, significant political or economic events can cause the share prices to diverge significantly. Examples include the third election of Xi in October 2022 or, more recently, the sluggish performance of the Chinese economy. See below the example of Ping An Insurance’s A and H share price.

In such instances, it becomes apparent that Chinese and international perspectives on these matters diverge significantly. Generally, my observation has been that foreign investors tend to overreact during these events, selling off their Chinese shares hastily. However, as time progresses, memories fade, and the share prices eventually stabilize and align once more. This pattern serves as one of the most reliable indicators I've encountered for measuring the differing sentiments between China and the rest of the world.

Efficient Markets: A Counterexample from China

As a mathematician—yes, I've just likely halved my readership with that confession— I'm naturally inclined towards the beauty and elegance of theories that explain complex phenomena with simple, universal principles. The hypothesis of efficient markets is one such captivating concept. It says that all known information is already reflected in stock prices, implying that it's impossible to consistently achieve higher returns without taking on additional risk.

At its core, this hypothesis assumes that market participants are rational, making decisions that lead to the most efficient allocation of resources collectively. The assumption that market players act rationally is, more often than not, a generous oversimplification. Over the years, some have argued that although individual investors might not always behave rationally, the market as a whole could still act rationally enough to validate the theory.

As Huxley said,:

Our beautiful hypothesis has been slain by ugly facts.

Take this efficient markets hypothesis!

Despite the Stock Connect program's efforts to unify the markets, there are persistent price discrepancies between dual-listed Chinese companies in Hong Kong and mainland China. According to the theory of efficient markets, such disparities should be quickly eliminated through arbitrage. However, these discrepancies continue to exist, not in obscure, illiquid companies, but in the largest and most closely followed stocks. For instance, consider Ping An Insurance, listed as $2318.HK in Hong Kong and 601318.SH in Shanghai, or the Postal Savings Bank of China, backed by Li Lu and Li Ka-Shing, listed as $1658.HK in Hong Kong and 601658.SH in Shanghai. Another example is Goldwind Science & Technology, trading under 2208.HK in Hong Kong and 002202.SS in Shenzhen, which currently has a 63% discount.

Exploiting Market Inefficiencies: A Practical Arbitrage Play

It's now evident, and further explanation on how to capitalize on this isn't necessary. If you like the underlying stock, simply hold the A-shares when the stock trades at roughly the same level, and then, whenever there's a steep decline in the H shares, switch to H-shares. Wait until the prices have equalized, then switch back to A-shares, and repeat the process.

Of course, this strategy carries its own set of risks, including the possibility of both H and A shares decreasing in value simultaneously. Alternatively, it might make sense to buy H-shares only when they are significantly undervalued and sell them as they approach the A-share price. In any case, I explore both methods to improve my returns.

Final thoughts:

Even if the arbitrage strategy I described doesn't capture your interest, the price discrepancies between dual-listed companies in Hong Kong and mainland China still offer significant insights. They serve as a gauge of the differing sentiments between individuals in mainland China and those abroad. Furthermore, these discrepancies underscore the limitations of the efficient market hypothesis.

"According to the theory of efficient markets, such disparities should be quickly eliminated through arbitrage"

I don't think that is what the Efficient Market Theory (EMT) says, I think that is an assumption about what it means. The EMT simply says that you cannot beat the market by using public information. So whilst the disparity between A and H shares seems irrational, an investor who went long H and short A would not have gained any excess return. The EMT does not say that market prices are "correct", just that public information cannot help you to correctly predict where prices will go in future.