Still Just a Rat in a Cage: Why Analyst Estimates Drive Investors Mad

Why JD, Alibaba, Pinduoduo and others drop after earnings—no matter the result.

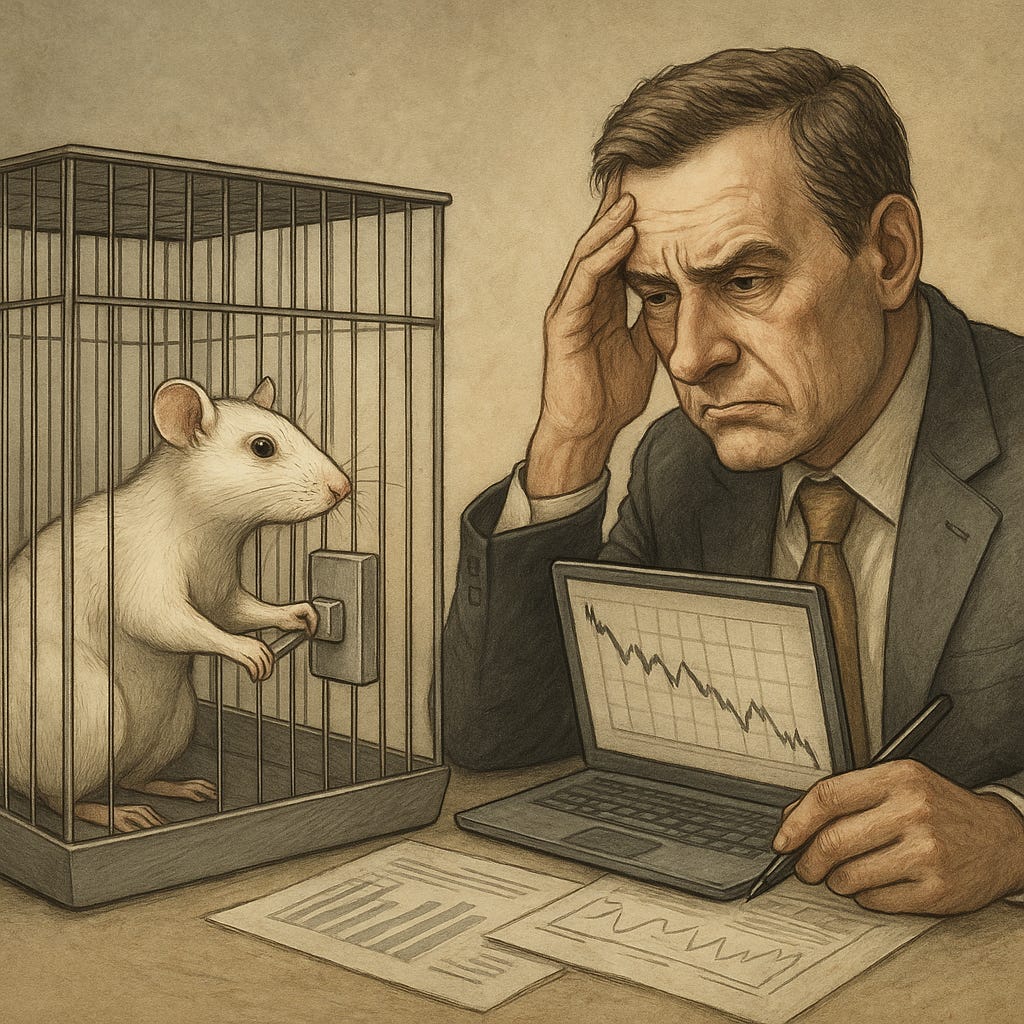

A recent study from Rutgers University (Crawford et al., 2024) set out to explore just how deeply randomness can mess with the mind. Lab mice were placed in a cage where pressing a lever would sometimes deliver food, and other times, a mild electric shock—completely at random. No pattern. No signal. Just the cruelty of randomness. After 18 days of this, the mice descended into madness, showing clear signs of anxiety: social withdrawal, compulsive behavior, hypersensitivity to noise. The shock itself was mild, that wasn’t the problem. The problem was the randomness of the outcome.

Why do I bring this up? Every quarter, I come across a tweet from someone clearly confused and frustrated. They’re complaining about the market: JD beat earnings, and the stock went down. Alibaba missed earnings, and the stock also went down. They must have felt like one of those mice from the Rutgers experiment—pressing the lever, hoping something will make sense. But instead, the randomness of the outcome took its toll—on their mood, and probably on their portfolio.

But the market wasn’t the problem. The real issue was that he based his expectations on one of the noisiest signals out there: the consensus estimate of analysts.

This isn’t meant as criticism of analysts. They’re doing exactly what they’re paid to do, and I don’t blame them for it. In fact, if I were in their position, I’d probably do the same. Still, that doesn’t change the fact that what they’re doing doesn’t make much sense.

When you think about it, the way these consensus estimates are produced is already absurd. A group of analysts, each updating their financial models every quarter, spend earnings calls begging the management to toss them a few scraps: margin guidance, revenue breakdowns, anything they can plug into their spreadsheets. Based on that, they adjust their EPS forecast for the next quarter, update their target price, and out comes the new “consensus.” It’s a ritual of precision built on guesswork. And judging a stock’s reaction based on whether it beats or misses that number? That’s like putting yourself in a cage, pressing a lever, and hoping you get food instead of a shock.

Being forced to forecast earnings every quarter puts analysts in a tough spot and often makes them sound quite silly on earnings calls. It makes sense from their perspective, they’re paid to produce quarterly estimates. But it makes far less sense when it comes to actually understanding a business.

Warren Buffett once said:

The idea of spending loads of time trying to guess how many iPhones or whatever it may be are going to be sold in a given three-month period to me, it totally misses the point… Nobody buys a farm based on whether they think it’s going to rain next year.

Many analyst questions don’t stem from genuine curiosity about the business, they come from the need to feed the DCF machine. You can hear it in the calls: it’s not about strategy, it’s about inputs. That’s one reason they’ve always struggled with Pinduoduo. The company doesn’t cater to analysts, doesn’t offer clean guidance, and frankly doesn’t care. And without anything to model, the forecasts tend to scatter and so does the frustration.

Having invested in stocks for a long time, I still haven’t figured out what a target price is supposed to mean. Ok I know it usually is a fancy way of expressing current price *1.2. But let’s be serious. It lacks all the information I would actually need. What’s the time frame? Are we talking about two months, one year, five years? And where are the error margins? A single number without any context is meaningless. At the very least, it should be an interval, not a single point.

When I analyze a stock, I think it’s far more useful to identify the three or four factors that truly drive the business. If I can’t identify those I don’t invest. If I can I focus on those. Build a few forward-looking scenarios. Assign rough probabilities to how things might play out as outlined in my article on John von Neumann. And then, as time passes, track which scenario is becoming more likely.

A funny side remark to end on: I’ve noticed that the management team at Tencent is increasingly annoyed by analysts’ questions. Lately, they’ve started saying it more or less directly, calling out when a question is stupid, sometimes right to the analyst’s face. On the flip side, they’re also quick to acknowledge when someone actually asks something smart.

In one of the recent calls, when an analyst asked about the high base in domestic game revenue and how that affects year-over-year comparisons, James Mitchell couldn’t hold back and simply replied with this.

I mean, I guess it's the curse of this kind of industry that if you do well, then people worry about the base effect a year later.

As if anyone besides analysts worries about a good quarter just because it makes next year harder to beat.

The important thing is this: Don’t try to react to every headline, every earnings whisper, every analyst target price. That’s how you end up like the rat in the cage.

Stay out of the cage. Watch the signal. Let the noise pass.

And as I was writing this, one line kept playing in my head: “Despite all my rage, I am still just a rat in a cage.” So yes, this article comes with a soundtrack. Smashing Pumpkins, “Bullet with Butterfly Wings.” Play it loud. Stay out of the cage.

Very well put. Great bonustrack as well!